Grow-your-own student lunches

September 4, 2013

It’s week three of our collaboration with the #betterbacktoschool brigade and David Suzuki Foundation’s Queen of Green.

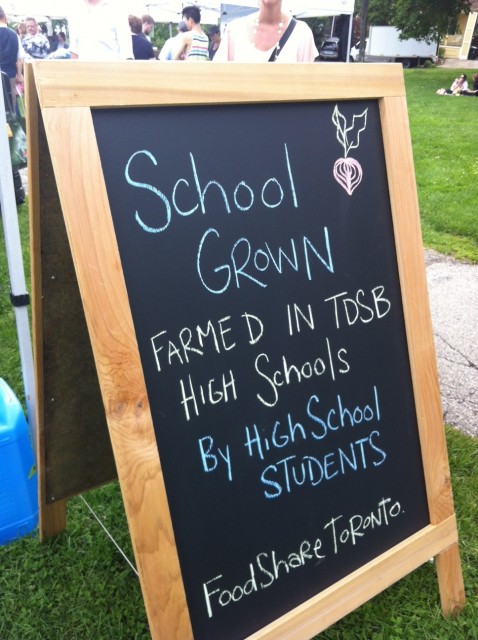

This week’s brigade theme is detoxing schools, so I interviewed one of the leading Canadian organizations working to get a major form of toxins – junk food – out of school cafeterias and student lunches. They’re also bringing nature into schools and students into nature by getting them to role up their sleeves and grow their own veggies. Actually, the farmers’ market near me in Toronto even has a FoodShare School Grown veggie tent where you can buy produce straight from students. Pretty awesome! Definitely inspired and hopefully inspiring for schools across the country.

Check out what Foodshare’s Katie German had to say….

Q&A: FOODSHARE’S KATIE GERMAN, COORDINATOR, FIELD TO TABLE SCHOOLS PROGRAM

Are our politicians putting their money where their mouth is on healthy food in schools?

Canada is one of very few G20 countries that isn’t committed to federal support for a student nutrition program. We’re fortunate to have municipal and provincial funding, which combined provides close to 20 per cent of the amount needed to support almost 700 programs across the city. But we’re still falling short, and only reach about a third of students.

You’ve had 10,000 kids go through the Field to Table Schools – have you developed an army of urban farmers?

Several high school students who’ve worked in our summer market gardens have gone on to study horticulture or culinary arts in college. But the real change is the growing and cooking skills that will stay with all these kids for life. They’re now equipped to grow their own food and feed themselves and their future families healthy food.

I just bought veggies from your new School Grown vendors at my local farmers’ market. What sparked this latest social enterprise?

We’re trying to move toward covering costs for our school market gardens and creating a more financially sustainable project. Also, selling to restaurants (like the George Brown Chef School and stores (like the Hogtown Cure) and at farmers’ markets has provided a meaningful context for our student farmers’ work. They’re committed to their work because they know the food is going to be bought and eaten.

Just when we thought farming was old-school, your Whole 9 Yards project showcases some crazy innovation.

We definitely love the old-school soil, seed and sun, but a little innovation goes a long way. We have a small tinker shop in the basement of FoodShare where our resident engineers and builders experiment and test ideas. Our File-A-Sprouts – old filing cabinets turned into sprouting boxes – are a great way to grow in the classroom. We’ve helped set up a classroom with a lettuce- and herb-growing fish farm stocked with 300 tilapia, and our bicycle-powered blenders have given new meaning to “enjoying the fruits of your labour” for students who can now drink their greens as part of a smoothie they’ve blended with their own energy.

Some say local food doesn’t always have a lower carbon footprint than imports. What’s FoodShare’s take?

One issue is how much energy it takes to produce something that wouldn’t naturally grow in our climate. Does it make sense to be heating hothouses for winter tomatoes? Maybe not. The good news is that urban farmers are able to take a less energy-intensive approach by making use of the urban heat island effect and growing with innovative systems. FoodShare’s on-site greenhouse is completely off the grid. Our school sites can produce into late fall and winter simply because the city is a few degrees warmer, and we use low-tech options like up-cycled cold frames and low tunnels. As we see more temperature extremes, sustainable urban farming systems will continue to flourish, and may also help mediate these weather extremes.

How has Canada’s approach to food changed since FoodShare’s founding in 1985?

The food movement has made great strides increasing both food consciousness and food access, but at the same time we know there are still folks who can’t afford to shop at farmers’ markets or organic grocers. Many don’t have regular nearby access to good, healthy food, and too many children have inadequate access to healthy food during the school day. We need to focus strategically on food justice as a priority.